Longs Peak

| Longs Peak | |

|---|---|

Longs Peak seen from the east at sunrise. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 14259.9 ft (4345.22 m)[1] NAPGD2022 |

| Prominence | 2940 ft (896 m)[2] |

| Isolation | 43.6 mi (70.2 km)[2] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 40°15′18″N 105°36′54″W / 40.2550135°N 105.6151153°W[3] |

| Geography | |

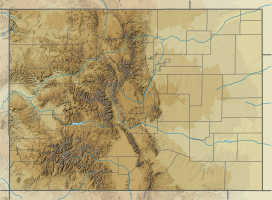

| Location | High point of Rocky Mountain National Park and Boulder County, Colorado, U.S.[2] |

| Parent range | Front Range, Highest summit of the Twin Peaks Massif[2] |

| Topo map(s) | USGS 7.5' topographic map Longs Peak, Colorado[4] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1868 by John Wesley Powell and party |

| Easiest route | Keyhole: Scramble, class 3[5] |

Longs Peak is a mountain in the northern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains of North America. The 14,256-foot (4345.22 m) fourteener is located in the Rocky Mountain National Park Wilderness, 9.6 miles (15.5 km) southwest by south (bearing 209°) of the Town of Estes Park, Colorado, United States. Longs Peak is the northernmost fourteener in the Rocky Mountains and the highest point in Boulder County and Rocky Mountain National Park. The mountain was named in honor of explorer Stephen Harriman Long and is featured on the Colorado state quarter.[3][2][4][a][6][7]

Description

[edit]

Longs Peak can be seen behind Mt. Meeker from Longmont, Colorado and more directly from Loveland, Colorado, as well as from most of the northern Front Range Urban Corridor. It is one of the most prominent mountains in Colorado, rising 9,000 feet (2,700 m) above the western edge of the Great Plains.

The peak is named for Major Stephen Harriman Long,[8][9] who is said to have been the first to spot the Front Range on June 30, 1820, during an expedition on behalf of the U.S. government.

Together with nearby Mount Meeker, with an elevation of 13,911 feet, the two mountains are sometimes referred to as the Twin Peaks (not to be confused with a nearby lower mountain called Twin Sisters).

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Longs Peak 40.2493 N, 105.6068 W, Elevation: 13,350 ft (4,070 m) (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 20.6 (−6.3) |

20.0 (−6.7) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

38.3 (3.5) |

50.0 (10.0) |

55.9 (13.3) |

54.1 (12.3) |

47.6 (8.7) |

35.9 (2.2) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 9.4 (−12.6) |

8.5 (−13.1) |

13.3 (−10.4) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

37.2 (2.9) |

43.5 (6.4) |

41.9 (5.5) |

35.5 (1.9) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

10.1 (−12.2) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −1.7 (−18.7) |

−3.0 (−19.4) |

1.4 (−17.0) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

13.9 (−10.1) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

−0.6 (−18.1) |

12.1 (−11.0) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.09 (78) |

3.25 (83) |

3.81 (97) |

4.95 (126) |

4.00 (102) |

2.18 (55) |

2.73 (69) |

2.60 (66) |

2.59 (66) |

2.71 (69) |

3.07 (78) |

3.03 (77) |

38.01 (966) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[10] | |||||||||||||

History of ascents

[edit]As the only fourteener in Rocky Mountain National Park, the peak has long been of interest to climbers. The easiest route is not "technical" during the summer season. It was probably first used by pre-Columbian indigenous people collecting eagle feathers.

The first recorded ascent was on August 23, 1868 by the surveying party of John Wesley Powell via the south side.[9] Addie Alexander was the first woman to summit Longs Peak in 1871.[11] Isabella L Bird also recounts an ascent in the 1870s in one of her letters (A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains)

The East Face of the mountain is 1,675 feet, steep, and surmounted by a 1,000 feet steep sheer cliff known as "The Diamond"[9] (so-named because of its shape, approximately that of a cut diamond seen from the side and inverted). Another famous profile belongs to Longs Peak: to the southeast of the summit is a series of rises which, when viewed from the northeast, resembles a beaver. Lumena Wortman Buhl was the first woman to summit the east face of the mountain.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Blaurock)

In 1954 the first proposal made to the National Park Service to climb The Diamond was met with an official closure, a stance not changed until 1960. The Diamond was first ascended by Dave Rearick and Bob Kamps that year, by a route that would come to be known simply as D1. This route would later be listed in Allen Steck and Steve Roper's influential book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.[12][13] The easiest route on the face is the Casual Route (5.10a),[14] first climbed in 1977. It has since become the most popular route up the wall.

Clark's Arrow (4th-class) is a climb to the summit of Longs named after John Michael Clark, who was a park ranger in Rocky Mountain National Park in the 1950s.[15] The oldest person to summit Longs Peak was Rev. William "Col. Billy" Butler, who climbed it on September 2, 1926, his 85th birthday. In 1932, Clerin "Zumie" Zumwalt summited Longs Peak 53 times.[16]

The record number of ascents to the summit of Longs Peak is 428, by Jim Detterline. Jim was a rescue Ranger in Rocky Mountain National Park. On October 23, 2016, he died in an accident while solo climbing. Jim rescued over 1,000 people in the mountains of Rocky Mountain National Park and he received the U.S. Interior Department's Valor Award. He also earned the title "Mr. Longs Peak".[17]

On June 6, 2016, a group of US Special Forces were rescued after members of the team suffered from altitude sickness.[18]

Mills Glacier

[edit]Longs Peak has one remaining glacier named Mills Glacier. The glacier is located around 12,800 feet (3,900 m)[19] at the base of the Eastern Face, just above Chasm Lake. A permanent snowfield, called The Dove, is located north of Longs Peak. Longs Peak is one of fewer than 50 mountains in Colorado that have a glacier.[20]

Climbing Longs Peak

[edit]

Trails that ascend Longs Peak include the East Longs Peak Trail, the Longs Peak Trail, the Keyhole Route, Clark's Arrow and the Shelf Trail. Only some technical climbing is required to reach the summit of Longs Peak during the summer season, which typically runs from mid July through early September. Outside of this window the popular "Keyhole" route is still open; however, its rating is upgraded to all "technical" as treacherous ice formation and snow fall necessitates the use of specialized climbing equipment including, at a minimum, crampons and an ice axe. It is one of the most difficult Class 3 fourteener scrambles in Colorado.[21] The hike from the trailhead to the summit is 8.4 miles (13.5 km) each way, with a total elevation gain of 4,875 feet. Most hikers begin before dawn in order to reach the summit and return below the tree line before frequent afternoon thunderstorms bring a risk of lightning strikes. The most difficult portion of the hike begins at the Boulder Field, 6.4 miles (10 km) into the hike. After scrambling over the boulders, hikers reach the Keyhole at 6.7 miles (10.5 km).

The following quarter of a mile involves a scramble along narrow ledges, many of which may have nearly sheer cliffs of 1,000 feet (305 m) or more just off the edge. The next portion of the hike includes climbing over 600 vertical feet (183 m) up the Trough before reaching the most exposed section of the hike, the Narrows. Just beyond the Narrows, the Notch signifies the beginning of the Homestretch, a steep climb to the football field-sized, flat summit. It is possible to camp out overnight in the Boulder Field (permit required) which makes for a less arduous two-day hike. However, this is fairly exposed to the elements and requires an ascent of 3300 ft over 6.4 miles with an overnight pack. Fifty-nine people have died climbing or hiking Longs Peak. According to the National Park Service, two people, on average, die every year attempting to climb the mountain. Less experienced mountaineers are encouraged to use a guide for this summit to mitigate risk and increase the probability of a summit.

For hikers who do not wish to climb to the summit, there are less-involved hikes on the peak as well. Peacock Pool and Chasm Lake are popular hiking destinations and follow well-maintained trails. It is also rewarding to hike just to the Boulder Field, the Keyhole, or the seldom-visited Chasm View—the ridge between Mount Lady Washington and the east face of Longs Peak. Camping is available at the Boulder Field and also on the lower portions of the mountain, such as Goblin's Forest next to the stream at the bottom. Technical climbers, with the correct permit, are allowed to use sites at the base of the East Face and at Chasm View. It is also possible to camp to the south of the mountain at Sand Beach Lake.

In addition to the standard "Keyhole" route, there are more serious and more technical climbs on Longs Peak. Climbers should seek qualified instruction; deaths on Longs Peak are an annual occurrence. Some of the more common routes are, in approximate order of popularity,

- North Face Cables route: This follows the Keyhole route to the Boulder Field, then ascends the North Face of the peak. It requires one or two pitches of low-5th class climbing, and is often downclimbed or rappelled by technical climbers since it is one of the fastest ways to ascend or descend the peak. In the early 20th century, enterprising guides installed a series of large steel eye bolts along this route, connecting them with a steel cable similar to systems in the Alps. The cables were removed in 1973 due to concerns about their appropriateness, but several of the bolts remain and are used as rappel anchors.

- Kieners Route: A traditional mountaineering climb that involves a climb of Lambs Slide (named after Reverend Elkanah Lamb who unintentionally slid down much of the route in 1871[9]), which is icy later in the season, then an exposed traverse of the Broadway ledge, and then low-5th class climbing.

- via the Loft: The Loft is the semipermanent snowfield between Longs Peak and its southeastern neighbor Mt. Meeker. The saddle provides access to either peak. One such traverse route is Gorrell's Traverse.[22] It is also possible to ascend to the saddle via Lambs Slide. The 4th class Clark's Arrow route is also accessible via the Loft, ascending from the West side of the mountain, and later connecting with the Keyhole Route.

- via the East Face: The East Face is the steep, 1,000 + foot (305 + m) wall that includes the Diamond and the Lower East Face. All climbs here are technical, from 5.10 to 5.13. It is also possible to ascend to the (climber's) left of the Diamond face proper. The routes on the right side of the Diamond are often aid climbed, and may require spending the night on the wall; the rock here can be very wet. Routes on the left side of the Diamond are usually free climbed. Only qualified climbers should attempt climbs on this face, and they should take into consideration the effects of altitude and alpine conditions in addition to the difficulty rating.

- via the Notch Couloir: This is a technical climb involving rock climbing and, at some times of year, ice climbing. The Notch Couloir is to the (climber's) left of the Diamond face.

Historical names

[edit]- "Highest Peak"

- Les Deux Oreilles (named by French fur traders), or "The Two Ears" (Longs Peak and Mount Meeker were both once named this)[9]

- "Longs Peak" – 1890[4] original name was Vasquez Peak, after Mountain man Pierre Louis Vasquez, who built his fort on the South Platte River in sight of the peak.

- "Long's Peak"

- Neniis-otoyou’u (or nesótaieux) (Arapaho language), or "the two mountains/guides" (Longs Peak and Mount Meeker were both once named this)[23][24]

In literature

[edit]Longs Peak is described in Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon as the location of a 16 feet (192-inch) reflecting telescope called "the Telescope of the Rocky Mountains", built for the purpose of tracking the Columbiad projectile on her flight to the Moon. Englishwoman Isabella Bird extensively describes her joy of visiting Estes Park and climbing Longs Peak during her 1872 solo trip from San Francisco to the Rockies in "A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains".

Gallery

[edit]-

Longs Peak from Road as photographed by Ansel Adams in 1941.

-

Albert Bierstadt, Estes Park and Longs Peak, 1876, Denver Art Museum was commissioned by the Earl of Dunraven for $15,000 (equivalent to $429,188 in 2023).

-

Longs Peak (center) and Mount Meeker (13, 911 ft. ASL, left foreground), October 2010.

-

A sunset over Long's Peak as viewed from Windsor, Colorado.

-

Longs Peak seen from Bear Lake.

-

Longs Peak seen from the north.

-

A view of the eastern face of Longs Peak, taken from the Twin Sisters trail

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ahlgren, Kevin; Van Westrum, Derek; Shaw, Brian (April 2024). "Moving mountains: reevaluating the elevations of Colorado mountain summits using modern geodetic techniques". Journal of Geodesy. 98 29. doi:10.1007/s00190-024-01831-8.

- ^ a b c d e "Longs Peak, Colorado". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "LONGS PEAK". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Longs Peak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Longs Peak Routes". 14ers.com.

- ^ Dziezynski, James (August 1, 2012). Best Summit Hikes in Colorado: An Opinionated Guide to 50+ Ascents of Classic and Little-Known Peaks from 8,144 to 14,433 Feet. Wilderness Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89997-713-3.

- ^ "Colorado Places: Their Native American Names". Center for Native American and Indigenous Studies (CNAIS). July 24, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Jessen, Kenneth (January 29, 2015). "Colorado History: William Byers among first white men to climb Longs Peak". Reporter Herald. Loveland Reporter Herald.

- ^ a b c d e Walter R. Borneman; Lyndon J. Lampert (1989). A Climbing Guide To Colorado's Fourteeners (2 ed.). p. 24. ISBN 0871087510.

- ^ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

To find the table data on the PRISM website, start by clicking Coordinates (under Location); copy Latitude and Longitude figures from top of table; click Zoom to location; click Precipitation, Minimum temp, Mean temp, Maximum temp; click 30-year normals, 1991-2020; click 800m; click Retrieve Time Series button.

- ^ Robertson, Janet, 1935- (1990). The magnificent mountain women : adventures in the Colorado Rockies. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803238924. OCLC 19847483.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Roper, Steve; Steck, Allen (1979). Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0-87156-292-8.

- ^ Jeff Achey; Dudley Chelton; Bob Godfrey (2002). Climb!: The History of Rock Climbing in Colorado. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0-89886-876-9.

- ^ "Casual Route". Mountain Project.

- ^ "Boulder Daily Camera".

- ^ Park, Mailing Address: 1000 US Hwy 36 Estes; Fridays, CO 80517 Phone: 970 586-1206 The Information Office is open year-round: 8:00 a m- 4:00 p m daily in summer; 8:00 a m- 4:00 p m Mondays-; Us, 8:00 a m-12:00 p m Saturdays- Sundays in winter Recorded Trail Ridge Road status:586-1222 Contact. "Hiking Essentials - Rocky Mountain National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Jim Detterline touched many lives as a climbing ranger in Rocky Mountain Nat'l Park - Alpinist.com". www.alpinist.com.

- ^ "Special Forces Rescued From Colorado's 14,000-Foot Longs Peak". NBC News.

- ^ "Mills Glacier, CO - N40.25556° W105.60972°". www.topoquest.com.

- ^ "Glaciers of Colorado". Glaciers of the American West. Portland State University.

- ^ "Home of Colorado's Fourteeners and High Peaks". 14ers.com.

- ^ A Climber's Guide to the Rocky Mountain National Park Area, Walt Fricke, 1971

- ^ "Center for the Study of Indigenous Languages of the West". University of Colorado Boulder. University of Colorado Boulder. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Longs Peak". Colorado Encyclopedia. Colorado Encyclopedia. July 27, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

For generations, Longs Peak played a part in the seasonal migrations, hunting practices, and cosmology of Ute and Arapaho Indians. The Arapaho called Longs Peak and Mount Meeker the "Two Guides," or nesótaieux, because of their physical prominence and role as landmarks for the entire region.

Further reading

[edit]- Stephen Trimble (1984). Longs Peak: A Rocky Mountain Chronicle. ISBN 978-0930487171.

- Paul Nesbit (May 21, 2015). Longs Peak: Its Story and a Climbing Guide. ISBN 978-0976825913.

- Bernard Gillett (2001). Rocky Mountain National Park: High Peaks: The Climber's Guide. Earthbound Sports. ISBN 0-9643698-5-0.

- Richard Rossiter (1996). Rock and Ice Climbing Rocky Mountain National Park: The High Peaks. Falcon. ISBN 0-934641-66-8.

External links

[edit]- "Longs Peak". 14ers.com.

- "Longs Peak Massif". Peakbagger.com.

- "Longs Peak, Colorado". Peakbagger.com.

- "Longs Peak". SummitPost.org.

- National Park Service guide to climbing Longs Peak

- VIDEO Climbing Longs Peak - DailyCamera.com